ROMAN ITINERARIES – CAMPO MARZIO DISTRICT – ITINERARY 14

CAMPO MARZIO DISTRICT – ITINERARY 14

By Campus Martius today we mean only the northern part of a vast plain, whose original boundaries ranged from the heights of the Capitol and Quirinal to those of the Parioli Mountains, with the Tiber River to the west and north as the extreme limit: the Campo Marzio District Itinerary 14 will give you the opportunity to star to discover this portion of Rome.

CAMPUS MARTIUS – THE ANCIENT TIMES

Objectively, the name of the District would suggest a massive and significant presence of areas dedicated to the god of war Mars, but in this sense we could be disappointed, because it happened exactly the opposite: while the Ara Pacis (Altar of Peace), a very important monument dedicated to the Pax Augustea, was placed in the District, Mars had to be satisfied with a cumulative place like the Pantheon that, being dedicated to all the gods, was supposed to contain also the simulacrum of Mars itself.

Since the Roman Republic, a very monumental public development took place on the Campus Martius. In 431 B.C. the construction of the Temple of Apollo, later called Sosiano, began; at the beginning of the III Century B.C. the Temple of Bellona was erected; the entire complex of the Argentine Tower Square occupied the space between the end of the IV and the beginning of the I Century B.C.; the Temple of the Muses dates back to the II Century B.C. and the porticoes and the Theatre of Pompey, the first of its kind to be built in masonry, to the middle of the I Century B.C.

It will be just between the current Argentine Tower Square and the Square of the Satyrs, where the Curia of Pompey was located, that in the Ides of March of 44 B.C. the assassination of Julius Caesar took place.

Progressively, many other monuments crowded the Campus Martius: the theaters (of Marcellus and Balbo), the great monuments sponsored by Agrippa, including the Baths and Aqueducts, the Pantheon, to conclude the ancient era with the Mausoleum of Augustus and the Ara Pacis.

CAMPUS MARTIUS – FROM THE MIDDLE AGES TO THE XVII CENTURY

At the end of the Middle Ages the District took on a strong international feature: around the Tiber rose a cluster of houses known as “Borgo Schiavonia“, mainly inhabited by Dalmatian and Illyrian people. The Greeks gave their name to a specific district where Gregory XIII had a seminary built for them. The Bretons took to live around the Church of St. Ivo alla Scrofa. Great Roman families built their houses in this district: the Orsini in Nicosia Square, the Colonna around the Mausoleum of Augustus, and then again the Counts, the Astalli, the Marescotti, the Margani, the Vitelleschi and many other families. Despite such a large presence of noble families, however, there is no record of particular towers and fortifications, replaced by the towers still existing in the Aurelian Walls, still standing at the end of the Middle Ages.

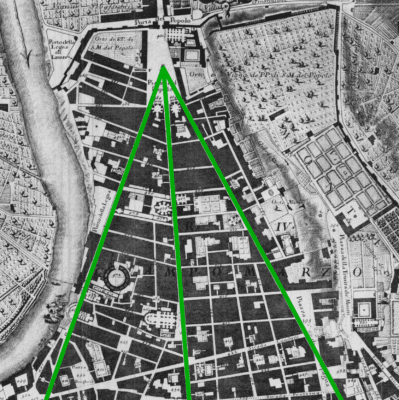

The current ward has a conformation developed from the urban needs of the first half of the 16th Century. At that time, the volume of commercial traffic on Rome began to arrive more from the north, through the Via Cassia and the Via Flaminia: this is why the People’s Gate began to increase its importance, becoming an authentic pivotal point of Rome’s commercial traffic and a strategic point for communications to the outside world, with the axis of the Via Flaminia that put the People’s Gate in direct contact with the Capitol.

It explains why the area of Campus Martius had to be immediately improved as soon as the Popes returned from Avignon, moving their headquarters from the Lateran to the Vatican, not just to be near the tomb of the Apostle, but for the security of the St. Angel’s Castle. After this phase, the Popes immediately realized how urgent the need to connect this area with the Vatican had become.

Pope Leo X, therefore, between 1513 and 1521 decided to draw a new road (later called Via di Ripetta, from the Port of Ripetta which stood on the banks of the Tiber) that would connect the People’s Gate with the connected fluvial dock and which immediately determined an urban development of social housing.

In 1584, Pope Sixtus V concluded this century of great projects and realizations by tracing Via Felice (from his baptismal name, Felice Peretti), which connected the Pincio Hill with the Lateran, passing by the Basilica of St. Mary Major.

CAMPUS MARTIUS – THE MODERN TIMES

The most radical changes took place to put an end to the periodic flooding of the Tiber: the master plan, implemented after 1876, led to the radical transformation of the Campus Martius, with the destruction of the Church of St. Lucy of the Tinta, the Port of Ripetta and its customs and wood warehouses. In more recent times, it was decided to isolate the Mausoleum of Augustus, sacrificing much of the surrounding urban fabric.

CAMPO MARZIO DISTRICT – ITINERARY 14

Start your journey from the Spagna Metro station (line A) and take the short Via del Bottino, so called by the small barrel, or a container of Virgin Water, documented by an inscription in Via della Fontanella Borghese: it may be that, next to the small fountain, there was a sort of counter, with the corresponding charge to the consumer. The remains of this ancient structure, datable to the 16th Century at the time of Pope Gregory XIII, were destroyed in 1902, for the construction of one of the elevators for the Pincio.

Via del Bottino – Piazza di Spagna – Trinità de’ Monti – Via Sistina – Via Gregoriana – Piazza Mignanelli

At this point, look around and admire the Square of Spanish Steps, with its irregular rectangle shape, its crowds, its monuments and the multitude of memories it arouses in all those who have crossed it. This is the place that welcomed the languid gaze of John Keats and inspired the brush of Van Wittel and Thomas Lawrence. The crowd disperses in the vastness of the square, coagulating in multicolored piles along the staircase or being sucked by the light descent of Via Condotti, while the last “botticelle” (the typical Roman carriages) stop at the sides of the large flowerbed that adorns the northern part.

The square looks like the union of two irregular triangles, narrowed by the axis of Via Condotti – Fountain of the Ugly Boat – Spanish Steps. The part where you are, at the end of via del Bottino, announces on the right the “ghetto of antiquarians” and the art galleries that characterize the most northern part of the district, radiating between via del Babuino and via Margutta. The other triangle is instead characterized by the presence of large palaces, such as the impressive Palace of Propaganda Fide, with its 17th Century structure and its monumental inscription, while on the western side there is since 1647 the seat of the Spanish Embassy, from which indirectly derives the name of the square.

THE KEATS AND SHELLEY MEMORIAL HOUSE

Next to the beautiful staircase you can see the 18th Century palace, also known as Casina Rossa (“Red Little House“), where is the Keats and Shelley Memorial House. Looking for health and inspiration, the English poet John Keats rented here in 1821 a small apartment located on the second floor, from which he could admire the staircase through a lovely balcony, and just in the small room overlooking the square Keats died a few months after arriving in Rome. The people of England bought the house collecting memories of their romanticism, expressed by poets in love with our country, such as Keats, Shelley, Byron and many others: letters, documents, drawings and many books embellish this beautiful and melancholy corner as those young men, far from their roots, must have been, to pursue their dreams.

THE BABINGTON’S TEA ROOM

On the opposite side of the Staircase, you can admire the centenary Babington’s, a place little frequented by the Romans, little familiar with the Tea Rooms, where peace reigns supreme, unscathed by the chaotic noises of the street. Perhaps this was the way it should have been the places of the past, places made for conversation, for relaxation, for a quiet meeting or for that “break” more and more necessary from the hectic modern life.

THE STAIRCASE OF THE SPANISH STEPS

Stop now in front of the majestic pearl of this square, the Staircase of the Spanish Steps. It looks like a waterfall of travertine, which widens, divides, overcomes obstacles, comes together again to erupt into several rivulets, while groups of people descend and climb its steps. It is the real living room of the young Romans, who have always used it as the perfect stage for their image and often for their ingenuity: the writer Dickens classified it as a living exhibition of models waiting to pose for the painters of the neighborhood, while after the war on the steps it was possible to find the tailors of the nearby ateliers sunbathing and looking for admirers.

To the painters and engravers Van Wittel, Tempesta, Falda and many others we owe the memory of how the square was arranged before 1723. The crossing of the 22 meters of difference in height existing between the Fountain of the Ugly Boat and the Church of the Trinity of the Mountains was in fact at that time managed by a winding and steep tree-lined path not easy to walk, since the clayey soil of the hill had to create many problems, especially on rainy days. Already in 1660 Cardinal Mazarino had thought to remedy this inconvenience, but without going beyond the execution of some drawings made by the architect D’Orbais. At the death of the cardinal, happened in 1661, the French nobleman Etienne Gueffier appeared on the scene: he wrote on his last will that he left as heir of his property the Convent of the Trinity of the Mountains, led by the Minims, providing that 400 scudi of the inheritance were destined to smooth the path for the stairway, demolishing certain buildings, and 20.000 were intended for the stairway itself.

Thanks to this amount of money, the work was started by Pope Innocent XIII, eager to connect the square below with the convent in a monumental and practical way. The Minims, however, fixed a particularly complex rule, that was to be able to observe with a single glance the entire staircase, to avoid the inconveniences that happened daily, consisting of obscenities and sexual intercourse that were consumed in the area, among the trees and bushes, even in broad daylight in the immediate vicinity of the church. The project for the staircase had therefore not to present dark recesses or hidden spaces.

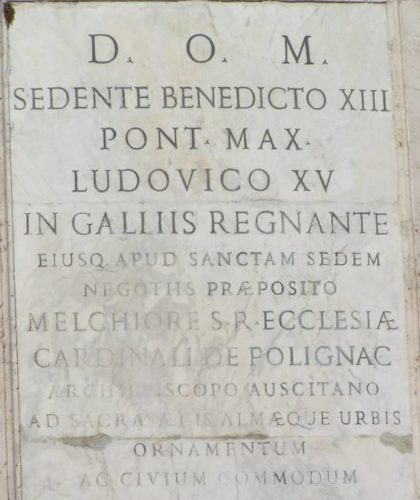

The work was finished in 1726, resulting in the end much more expensive than it should have been (as it happens very often): the deficit was covered by the King of France Louis XV, but unfortunately the problems did not end there. On September 26th 1728, there was a ruinous fall due to the collapse of the embankment on one of the sides of the staircase, on which already visible cracks could be seen. The subsequent judicial investigation revealed that bad materials had been used, used without sufficient foundations, and the architect, bricklayers and stone cutters were considered responsible. The architect Valeri, who was in charge of the investigation, bitterly explained that another 20,000 scudi were needed for the repair, but the cost was so high that the work was not continued for several years.

The Pope put pressure on the French court, and the King of France was forced to cover again the deficit. The author of the Staircase, whose fame was greatly diminished by all these problems, was Francesco De Santis, a little known architect who gained fame and glory thanks to his creation. De Santis was inspired by the project of another famous architect of Rome, Alessandro Specchi, following his project for the Port of Ripetta (now disappeared). Unfortunately, because of the chaos caused by the collapse of the side of the staircase, and also because of the brevity of his life, Francesco De Santis did not work in Rome anymore.

The staircase consists of 136 steps in total, divided into eleven dozen plus four. More or less in the middle, there is an inscription that defines this work as “magnificent” and mentions Stefano Gueffier, ambassador to the Holy See, as its financier. On the top shelf, before the end of the staircase, a second inscription states that King Louis XV (called Ludovico) built this “marble staircase” in the year of the Lord 1725.

THE FOUNTAIN OF THE UGLY BOAT

The fountain at the bottom of the Spanish Steps has this curious nickname because of its shape, and is linked to a centuries-old problem that plagued Rome until the end of the nineteenth century, namely the flooding of the Tiber River, which, during torrential rains, was flowing out of its riverbed literally flooding the entire city of Rome. In 1598, in particular, the flood of the Tiber was so violent that several boats detached from their moorings, ending up dry in various parts of Rome, including this one.

The construction of the fountain is however connected to another explanation, much more concrete. Although the Aqueduct of the Virgin Water had been fully reactivated, in fact, the inhabitants of the Campus Martius could enjoy only a small part of it, because it flowed underground without any surface water supply. At this point Pope Urban VIII commissioned Pietro Bernini, father of the more famous Gian Lorenzo, to build a fountain in memory of the famous flood of 1598, placing it at the base of the path that climbed the Pincio Hill (the staircase, in fact, had not yet been built).

Pietro Bernini chose to realize in stone the shape of one of the typical boats that in Rome were used for the river transport of wine barrels: that’s why the boat has particularly low sides, to facilitate the embarkation and disembarkation of wine barrels. However, the sculptor immediately realized how the low pressure of the aqueduct did not allow the realization of small waterfalls or spectacular water games: the solution of the problem was found by digging an oval tank under the boat, filling it with water and giving the effect of a boat, very ruined, in the act of sinking.

On both sides, aft and bow, you can see two sculptures of a sun with a human face and two papal coats of arms, with the tiara and the three bees, the heraldic symbol of the family of the Pontiffs, the Barberini. According to tradition, it was the very young Gian Lorenzo who sculpted these decorations.

This fountain is usually the meeting point for the City Centre Tour of Rome Guides, so we love it!

THE SALLUSTIAN OBELISK

Climb all the steps to find yourself at the end on the Square of Trinity of the Mountains, slightly irregular, squeezed between the final balustrade of the Spanish Steps, the other staircase that gives access to the church and the obelisk.

The Sallustian Obelisk is surmounted not only by the cross, but also by the lily of France. The obelisk comes from the Horti Sallustiani, and more precisely from a hippodrome that must have been located in that huge complex, and was placed at this location after several vicissitudes. Ruined at the time of Alaric, this obelisk remained unknown until 1527, when it was found: Pope Sixtus V wanted to raise it in front of the Church of St. Mary of the Angels, Pope Clement XII in 1754 wanted it first in front of the main facade of St. John Lateran and then, alternatively, in front of the Holy Stairs. In 1788, finally, Pius VI gave it its present arrangement after overcoming objections from the Minims resident in the convent, since they were not entirely persuaded of its stability on a vaguely friable ground. In 1789, a terrible year for France, it was settled in the place where you see it today by the architect Giovanni Antinori. The hieroglyphs that adorn it are a simple imitation of those found on the other obelisk, much more majestic, which adorns the People’s Square.

THE UPPER SQUARE

Looking around, you will see many tourists looking for an impressive photo and several taxi drivers in front of a well-known luxury hotel, the Hotel Hassler. The cabs, unfortunately, ruin a bit the view of the small white loggia of the Zuccari Palace, which stretches towards the square with the entrance (by Filippo Juvarra) of this elegant “royal palace”, inhabited by Queen Maria Casimira of Poland (widow of the liberator of Wien Giovanni Sobieski) since 1702, who had a small private theater set up inside, where the composer Domenico Scarlatti also performed.

The palace subdivides, with a perfect Y, via Sistina from via Gregoriana. The first one appears and disappears as far as the eye can see, one up and down after the other, but always perfectly straight towards the other obelisk in the Esquiline Square; the other, downhill, is dampened above Via Capo le Case.

THE CHURCH OF TRINITY OF THE MOUNTAINS

The name “of the Mountains” of the church was given not only by the position of the church (in Rome every hill, even the most modest, is called “mount” or “hill”) but also by the need to distinguish it from the other Trinity, which we could call “del Campo” (“of the Field”) and which is located at the end of Via Condotti near Largo Goldoni.

THE HISTORY OF THE CHURCH

More than to the Holy Trinity, this church should be dedicated to St. Francis of Paola: the religious complex originated in fact from the relationship between this Saint and King Louis XI, who was probably considered miraculous by St. Francis himself. The relationship between the two characters, and the role of St. Francis of Paola and the Order of the Minims in the French presence, inspired strange parallels between the Calabrian saint and St. Louis, as can be seen from the bas-reliefs of the two herms placed on capitals that adorn the access stairs.

The original inscription, placed at the center of the wall of the access staircase, just in front of the still existing obelisk, spoke about the royal munificence and the decisive contribution of the Order of the Minims. In 1816, however, it was partially modified, covering with coats of arms and friezes the part related to the religious order, to give the merit of the foundation of the church only to the royal munificence: obviously, the King of France Louis XVIII did not have the same passion of his ancestor Louis XI towards the Minims.

However, the history of the church has much older origins. In 1495, with the favor of Pope Alexander VI, the King of France Charles VIII had already purchased a part of the Pincio Hill from the Barbaro family, who owned it at that time. The hill at that time was only mostly uncultivated, with some modest vineyards cultivated among the ruins of the ancient Villa di Lucullo. Still the French, and specifically Francis I, accelerated the process of canonization of St. Francis of Paola, which took place in 1519: it clearly showed how the Order of Minims would not have reached the importance it had without the French support.

In 1550 the cloister was completed too, but to see the actual façade you had to wait until 1584. Built by the architects Giacomo Della Porta and Carlo Maderno, the façade has a vaguely gothic layout, characterized as it is by the two bell towers, in which we wanted to see a vague with the cathedrals of Reims and Strasbourg.

THE DECORATIONS OF THE CHURCH

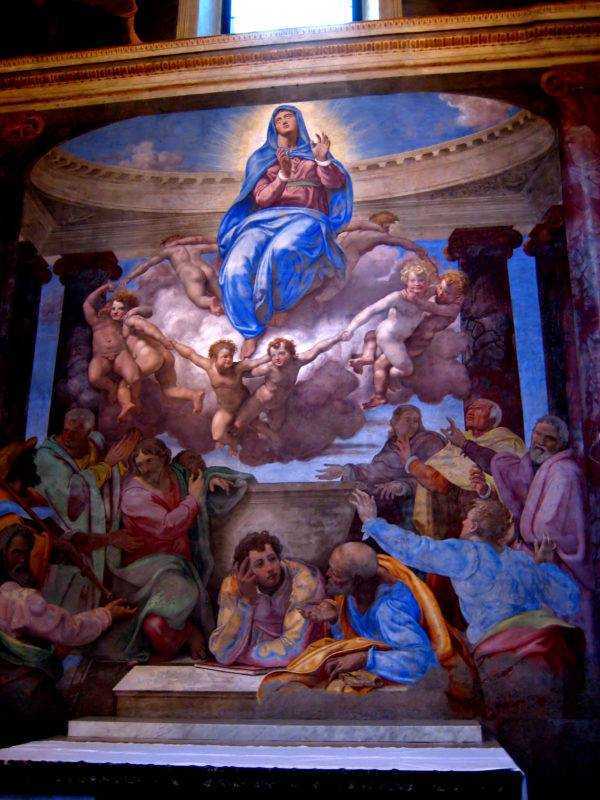

The interior has a single nave with side chapels, and seems rather modest because of the simple ceiling and the bronze gate that divides it into two parts. Yet this church is remarkable for the paintings it houses: among these, the prominent place on the left is the Orsini Chapel, decorated by the famous “Deposition” painted by Daniele da Volterra, on a design traditionally attributed to the genius of Michelangelo Buonarroti. Go also in front of the Massimo Chapel, the fifth on the left, where three painters of great fame alternated in the pictorial decoration: Perin del Vaga, who began to depict the “Death of the Virgin“, “the Assumption” and “Dead Christ supported by the Eternal Father“; died in 1562, the work was continued by Taddeo Zuccari; when he died too, in 1566, his brother Federico Zuccari arrived and completed the work.

In the course of this experience, Federico Zuccari fell so much in love with this place that he decided to build his house here, which you will see in a little while once you reach Via Gregoriana.

VIA SISTINA

Now take via Sistina, which was opened with the name of via Felice in 1585 by Pope Sixtus V (real name Felice Peretti). It represents a sort of rectilinear road that, even if with different names, goes beyond the Pincio, Quirinale, Viminale and Esquilino hills, reaching as far as the Lateran, now surpassed by the Vatican as papal seat for military reasons but still one of the historical hubs of the city. Via Sistina is full of high-level stores and high-class hotels. Axis of one of the most famous urbanistic perspectives of the city (as previously underlined), it has an elegant and refined atmosphere.

The stretch that falls within the perimeter of the Campus Martius District is short, but for this reason not rich in memories. At house number 104 an inscription remembers the presence of Hans Cristian Andersen between 1833 and 1834: here the well-known writer was inspired by the novel “The Improviser“.

On house number 64, instead, a plaque of 1872, placed by the Municipality of Rome, remembers how this palace was the home of the painter Federico Zuccari (as we have seen, one of the artists who decorated the nearby church). The quiet air of the Zuccari Palace should not be deceiving: only this side is sober and formal, a choice made in order to accentuate the originality of the other façade. It is a curious game of sacred and profane alternations, conformism and protest, sobriety and originality.

VIA GREGORIANA

To discover the other side, go back and take Via Gregoriana, arriving at number 30. Observe what you have before your eyes: an effect of great extravagance, a poetic whimsy, very similar to the monsters visible at Villa Orsini in Bomarzo, with the façade animated by large surrealist faces, whose wide open mouths form the entrance door and side windows.

The project in fact turned out to be very expensive, and at his death Federico Zuccari left a lot of debts, without being able to realize his utopian dream of creating, inside the Palace, an academy of figurative arts. On the occasion of the Grand Tour, the Palace was converted into an inn for artists, hosting in its rooms Johann Winckelmann and Jacques Louis David; it was finally purchased by Enrichetta Hertz who, thanks to her considerable bequests to the German government, allowed the foundation of the Hertziana Library, which still owns the entire complex.

Adjacent to the Zuccari Palace there was the house of the painter Salvator Rosa, which also extended between Via Gregoriana and Via Sistina, more or less in the position of the present Stroganoff Palace, with a beautiful rusticated door that supports a small loggia: Raphael Mengs died in 1779 and the writer Stendhal lived there for a few months.

THE TOMATI PALACE

Unfortunately, examining the individual buildings facing the street, it is easy to see how all or almost all of them underwent radical transformations in the second half of the 20th Century, saving only here and there fragments of the original structures, as in the atrium of the Tomati Palace. It was in this building, later called the Buti House, that leading exponents of the cultural world of the so-called “ultramontani” found hospitality: one of the most famous among them was the philologist Wilhem von Humboldt who, together with his wife, gave life to a lively cultural center in which the poet Friederike Brun, the sculptor Berthel Thorvaldsen and the writer August Kestener, also known for the extravagance of his 16th Century clothing.

It was Kestener himself who founded the German Archaeological Institute here and encouraged the pictorial movement of the Nazarenes, a new Catholic-purist pictorial movement that was successful in Rome. Kestener, who died in this palace in 1853, rests in the Non-Catholic Cemetery next to the Cestia Pyramid, but shortly before his death he published the “Romische Studien” portraying all the personalities who passed through the Tomati Palace, thus providing us with a very valid memory of personalities such as Paganini, Rossini, Thorvaldsen and many others.

The Square of the Trinity of the Mountains is therefore, after all, a piece of foreign land. The Church of the Holy Trinity (with the annexed convent and school) is French, the Zuccari Palace is German, and even the solemn staircase, except for the architect, was financed with non-Italian money.

Go down at this point the one hundred steps of the Mignanelli Ramp, which no foreign State can claim as its own, and reach the Mignanelli Square, which looks like a widening, a sort of appendix, of the southern part of the Spanish Steps. If it were not older than three centuries or so, it would be said to be built to give a better perspective to the latter.

The Mignanelli family belonged to the Sienese nobility, but since a cardinal’s hat often made much more than a noble title, the family preferred to leave Siena for Rome at the end of the 15th Century, settling in 1615 in the palace present in this square, which for the Romans has always been known more for the presence of the Direct Tax Offices than for the presence of the palace itself. The building, erected in the 16th Century by the architect Moschetti (the only work he did in Rome) was initially set on only two floors, plus a third, which occupied only half of the entire length of the building, creating a sort of turret. The current appearance, however, dates back to 1887 and was designed by the architect Andrea Busiri Vici.

The Institute of the Propaganda Fide, owner of the building, first leased it to the Roman Bank and then to the French Club: today the building is famous for being the residence of the famous fashion designer Valentino and the headquarters of his fashion house. Although restored by the great fashion designer, visiting the interior leaves a melancholy aftertaste: the ancient staircase of honor has been remodeled, and the famous fresco on the episodes related to the “Foundation of Rome“, such as the sighting of vultures by Romulus and Remus and the killing of the latter, is cut off.

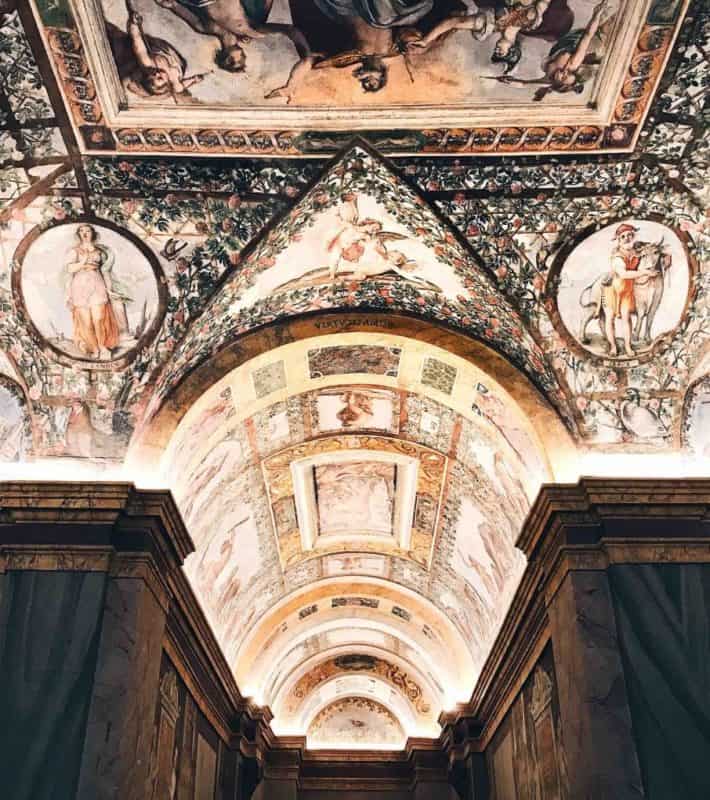

THE SPANISH EMBASSY TO THE HOLY SEE

On the other side of the square, stands the Spanish Palace that gives its name to the square: it is the seat of the Spanish Embassy to the Holy See, and its diplomatic destination dates back to 1647. Renovated by the architect Antonio Del Grande, it reserves many surprises for the lucky ones who have the chance to visit it, including the frescoes by Pier Leone Ghezzi, Vicente Lopez and Mario dei Fiori. The building also preserves an 18th Century theater, thus underlining the lively worldliness that characterized its inhabitants.

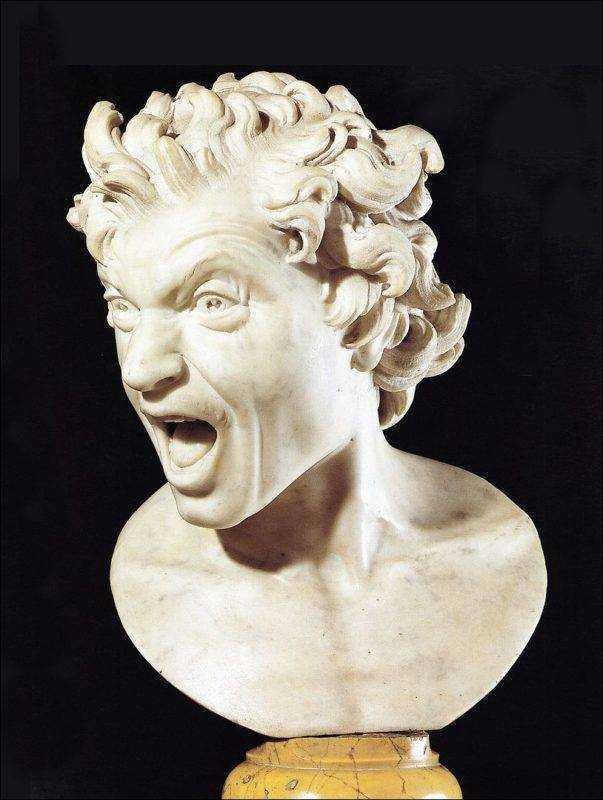

The masterpieces of the Palace, however, are the two heads carved by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, the Damned Soul and the Blessed Soul, baroque masterpieces marked by a secret: the damned soul, furious and screaming, would be a self-portrait of the famous baroque artist.

THE COLUMN OF THE IMMACULATE CONCEPTION

Located in front of the Spanish Embassy, the Column of the Immaculate Conception is one of the most important Christian monuments of Rome dating back to modern times. Actually, the column in cipollino marble has a much older history, having come to light during the works for the Benedictine Sisters convent near St. Mary in Campus Martius: it is 11 meters high and has a diameter of about one and a half meters. Including the statue at the top, the entire monument is actually just under 30 meters high.

After various vicissitudes, deriving from the desire to use it in the most disparate places, Pope Pius IX decided to use it to celebrate his contrasting dogma of the Immaculate Conception, pronounced on December 31th 1854. The column was hoisted on December 25th 1856 by a real army of firemen on a high octagonal base adorned by four figures of prophets (Moses, David, Isaiah and Ezekiel) and by bas-reliefs representing episodes of the “Life of the Madonna“.

A few years later, on the top of the Column, was placed the bronze statue of the Virgin Mary, made by the sculptor Giuseppe Obici, who used as a model his mother-in-law instead of his wife (thus triggering the gossip of Roman citizens) and who also modeled the group below, composed of the four evangelists who support the globe that serves as a pedestal to the statue of the Madonna.

Every December 8th, the Fire Brigade respects the tradition of placing a wreath of flowers around the arm of the Virgin Mary.