ROMAN ITINERARIES – TREVI DISTRICT – ITINERARY 6

TREVI DISTRICT – ITINERARY 6

After having discovered all the secrets of the most famous fountain in the world and its close proximity, the Itinerary 6 of the Trevi District will allow you to immerse yourself in the architectural structure of the lower part of the District, characterized by the presence of narrow streets and tiny alleys that branch out from the fountain in the direction of the Roman Forums, bordering majestic noble palaces and ancient churches, overlooking vast squares with centuries of history.

The route is jagged and therefore covers the entire area between Via del Corso and the slopes of the Quirinal Hill, with the exception of the Forums, which are not included in the borders of the Trevi District.

Piazza di Trevi – Via delle Muratte – Via delle Vergini – Via dell’Umiltà – Via dei Lucchesi – Piazzetta dell’Oratorio – Via Minghetti – Via San Marcello – Piazza dei Santi Apostoli – Via IV Novembre – Largo Magnanapoli – Via della Pilotta – Piazza della Pilotta

THE CHURCH OF ST. RITA

Always starting from Trevi Square, you can take Via delle Muratte, which derives its name from the property of the pontifical vicar Renzo Musciani, nicknamed “Amoratto“.

The street, lined with 17th and 18th Century buildings, comes out on Via delle Vergini, so called because of the presence of the convent annexed to the Church of St. Rita from Cascia, owned by the Augustinian Nuns. The first church with this name was once located in the area now occupied by the Pallavicini-Rospigliosi Palace, and it was demolished in 1615 by the powerful Cardinal Scipione Borghese, nephew of Pope Paul V, to replace it with his palace.

The church was then entirely rebuilt on the slopes of the Quirinal Hill, in the place where it currently stands, not far from St. Mary of Humility, and was once again run by Augustinian Nuns until 1870. After the Taking of Rome the nuns were expelled, and the church was used as a public office, to be reopened to the public only around 1970.

The graceful and simple façade has a large rectangular window and ends with a triangular tympanum. The small Greek cross-shaped interior has no particular attractions, apart from the pleasant 17th Century frescoes that cover the vault of the presbytery, the small dome and the lantern.

THE ORATORY OF THE CRUCIFIX

The church marks the point where Via delle Vergini crosses Via dell’Umiltà, which also takes its name from a monastery, that of St. Mary of Humility, of which only the church remains today. It was laid out in 1611 by Pope Paul V (as can still be read in an epigraph on the corner with Via dei Lucchesi), and until the 19th Century the first section was called “Via dei Tre Ladroni” (Three Thieves Streeet), because of the sign of a tavern.

The street leads to the small square of the Oratory, which takes its name from the Oratory of the Crucifix, whose 16th Century façade overlooks the square.

The history of this monument, little known but of considerable interest, is rather curious, and begins with a 15th Century wooden Crucifix, now kept in the nearby Church of St. Marcellus (it became very famous for the controversy that arose from its use during the mass of Pope Francis I in St. Peter’s Square, during the Covid19 epidemic).

When in 1519 the Church of St. Marcellus was destroyed by a violent fire, only the Crucifix survived; the astonished people cried out for the miracle, and began to venerate it, so much so that three years later, during a plague epidemic, they took it in procession to St. Peter’s. As a result, after a short time the disease disappeared; so it was decided to found a confraternity dedicated to the Holy Crucifix, which was approved in 1526 by Pope Clement VII, with the aim of assisting pilgrims, helping beggars, curing the sick ones and also offering the dowry to poor girls so that they could get married.

The Pope also decided to build a new oratory, entrusting the project to the architect Giacomo della Porta, who built it between 1562 and 1568, also demolishing some houses in front of the building and creating the Little Square of the Oratory.

After a sacking in 1798, the building was abandoned and was then restored twice, in 1821 and 1879. The elegant façade with two orders has a quite animated layout: in the lower order there is an austere portal preceded by a short staircase and surmounted by a triangular tympanum, while a cornice divides the first from the second order. In the centre you can see a large tombstone with an inscription commemorating the Farnese cardinals, the patrons who allowed the construction of the monument.

The interior is worth a visit: the large rectangular hall has walls entirely covered with Mannerist frescoes that have as their object the discovery and exaltation of the Cross. Executed around the last quarter of the 16th Century, they are the work of painters such as Pomarancio, Paris Nogari, Baldassarre Croce, Cesare Nebbia and Giovanni de Vecchi.

THE SCIARRA GALLERY

Let us now move on from Mannerism to Eclecticism. On the right of the oratory is the Sciarra Gallery, one of the most unique examples of the Roman Belle Epoque.

The Gallery looks like a square room, entirely frescoed and covered by a large skylight. It is a part of the great Sciarra Palace, which hosted, around 1885, the editorial staff of a singular magazine, “Cronaca Bizantina“, directed by Gabriele d’Annunzio. Around the magazine, which obviously had nothing to do with Byzantium, numerous cultural figures had gathered, including Prince Maffeo Sciarra, who decided to radically transform the part of the palace where the magazine was located, and entrusted the reconstruction to the architect Giulio De Angelis and the painter Giuseppe Cellini, author of the frescoes, which have as their subject the vision of the woman and her role in society at that time. Bride, mother and angel of the home, the woman is thus represented in a series of daily scenes, such as wedding attire, banquet, conversation and musical entertainment.

Higher up, inside sophisticated pavilions of floral taste, other women are painted, impersonating the virtues to which the inscriptions inside the upper cartouches allude: fidelity, justice, humility and so on. This is a real reinterpretation of Michelangelo’s cycle of the Sybils in the Sistine Chapel, according to the taste of the Liberty style.

Now take Via di San Marcello and, after a few meters, you will find yourself in front of the tiny chapel of the Virgin of the Little Arch, an admirable work of the architect Virginio Vespignani, who built it in 1851. Inside, note the frescoes by Costantino Brumidi, known for having frescoed the Capitol of Washington, and the image that gives its name to the little church, painted on majolica stone by Domenico Muratori. It is venerated because it seems to have moved its eyes twice a century later, in 1696 and 1796.

SAINT APOSTLES’ SQUARE

Via di San Marcello comes out in Saint Apostles’ Square, overlooked by the church that gives it its name surrounded by majestic noble palaces.

THE DELLA ROVERE PALACE

On the left side of the basilica is the Della Rovere Palace, attributed to Giuliano da Sangallo, who would have built it around 1478 for Cardinal Giuliano della Rovere, who later became Pope Julius II. The building, which has a typical 15th Century façade, is however the extension of a previous building, begun in 1460 by Cardinal Bessarione and later enlarged and restructured by the nephew of Pope Sixtus IV, Pietro Riario.

When he died in 1474, the palace passed to Giuliano Della Rovere, who rebuilt it and had his name engraved on the architrave of the windows, in an inscription recalling his cardinalate at St. Peter in Chains.

Inside there are two cloisters, lined up one behind the other: the first dates back to the end of the 15th Century and has a column in the centre surmounted by a statue of the Virgin Mary, while the second is slightly later (the presence of the coat of arms of Julius II allows us to date it to the years immediately after 1503) and is partially occupied by a simple fountain.

Along the entire wall bordering the left wall of the church are a series of sepulchres, including those of Cardinal Bessarione, Grand Duke Leopold of Tuscany and the great Michelangelo, who had his first burial in 1564 in this church, before being buried definitively in Santa Croce in Florence.

THE COLONNA PALACE

On the other side of the church, you can see the imposing bulk of the gigantic Colonna Palace, whose origins date back to the Middle Ages, when the Colonna family settled in a tower near the Forum of Trajan. The family obtained great glory in 1417, with the election of Pope Martin V, a member of the Colonna family, to the papal throne. The Pope then had the first nucleus of the building next to the church built, which a few decades later also incorporated another 15th Century construction, the building of Giuliano della Rovere who, once he became Pope, donated it to Marcantonio Colonna.

From that moment on, the immense growth of Colonna Palace began, hosting in its increasingly sumptuous halls a series of historical events of great interest, including the signing of the pact between Clement VII and Charles V or the abdication of Charles Emmanuel IV of Sardinia.

If in the 16th Century the building was similar in appearance to a fortress (a large quadrilateral defended by crenellated walls and arranged around the garden), in 1620 it was entirely rebuilt in more noble forms by Filippo Colonna, who began the construction of the great Gallery.

The present appearance of the palace was actually born a century later, in 1730, thanks to the project of the architect Niccolò Michetti, who created a luxurious environment around the large courtyard, in the middle of which was placed, on top of an elegant pedestal, a high Ionic column, in reference to the family coat of arms.

THE COLONNA GALLERY

Inside the palace, still owned by the Colonna princes, you can visit the amazing Colonna Gallery (open on Saturday morning: visit it booking the Museums and Galleries Tour) founded by Girolamo I Colonna, built by Antonio Del Grande and Girolamo Fontana, and inaugurated in 1703.

The salons, splendidly furnished with period furniture, have frescoed ceilings: particularly remarkable is the salon, where on the vault Giovanni Paolo Schor painted “the Battle of Lepanto” and “the Triumph of Marcantonio Colonna“, commander of the papal fleet that won the victory against the Turks at Lepanto in 1571.

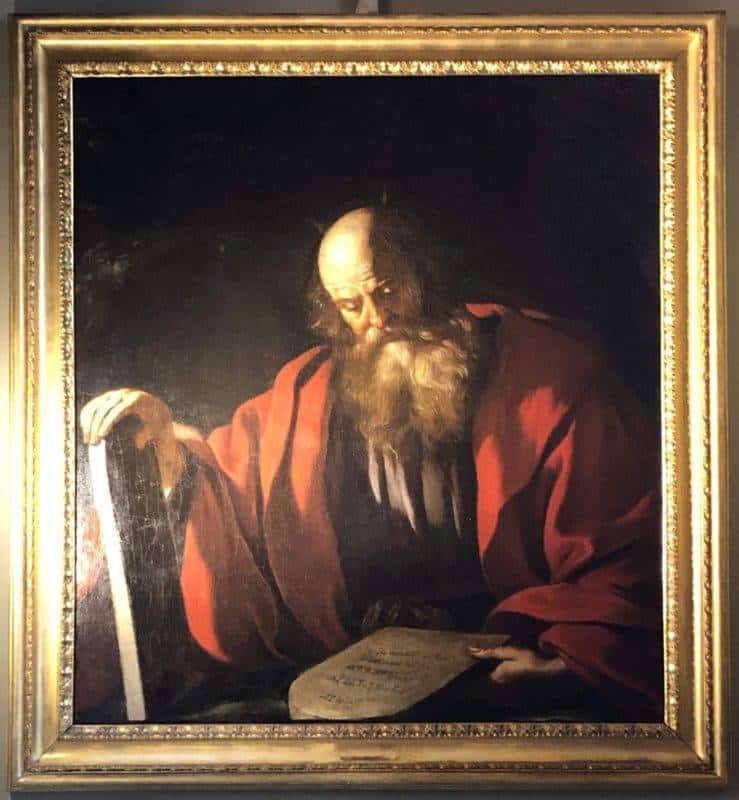

On the walls, you can admire masterpieces by Tintoretto, Bronzino, Carracci and many other painters from the 15th to the 17th Century.

THE ODESCALCHI PALACE

On the opposite side of the square, observe the majestic Odescalchi Palace, located in front of the basilica. It occupies the area where the turreted building of the Benzoni family stood, then passed to a branch of the Colonna, who sold it in 1622 to the Ludovisi: the family contacted the architect Carlo Maderno to enlarge it and, when the palace passed to Cardinal Flavio Chigi in 1661, it was arranged by Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

At the end of the 17th Century the building, now completed, was rented to the Odescalchi, who just five years later hosted an illustrious visitor, Queen Maria Casimira of Poland, widow of King John III, who stayed there for a few years.

In 1745 the Odescalchi finally decided to buy it and, to celebrate the purchase, they immediately had it enlarged by two illustrious architects, Nicola Salvi, author of the Trevi Fountain, and Luigi Vanvitelli; this enlargement doubled the size of the building, at the expense of the beautiful back garden, which had survived until then.

The façade, of which only the middle part is attributable to Bernini, has a rather sober and slightly gloomy appearance. Through the two portals flanked by columns and surmounted by balconies one enters the large rectangular courtyard, built by Maderno, surmounted by simple windows inserted inside closed arcades.

In the middle of the courtyard, on a square pedestal, stands a naked virile statue, certainly of Roman times, while eight other statues are placed at the sides of the courtyard, two on each side. In front of the entrance, at the end of the courtyard, there is a small fountain, decorated with the Odescalchi coat of arms. In a shell-shaped chalice, two dolphins and an eagle throw water, which is then poured into a second basin below.

THE BASILICA OF THE HOLY APOSTLES

The Basilica of the Holy Apostles has very ancient origins: tradition says that it was founded by Pope Julius I, in the 4th Century, but it is more likely that it was founded in the 6th Century by Pope Pelagius I, who dedicated it to Saints Philip and James.

Completed by a third Pontiff, John III, between 561 and 574, it was restored just two centuries later under Stephen V, between 885 and 891.

In the dark years that followed, almost nothing is known about the history of the basilica: it reappeared in the chronicles immediately after the Avignonese captivity, thanks to Pope Martin V, a member of the Colonna family.

The church was restored once again at the end of the 15th Century by Pope Sixtus IV, who asked an illustrious architect, Baccio Pontelli, to build the beautiful nine-arched portico that precedes the façade and represents a typical example of late 15th Century architecture in Rome: admire the mighty octagonal pillars with the leafy capitals of the first order, while the arches supported by slender Ionic columns of the second order were closed in the second half of the 17th Century by the architect Carlo Rainaldi, who designed the windows with the characteristic tympanum adorned with a winged angel, and had the statues of “Christ accompanied by the Twelve Apostles” installed on the attic around 1681.

The history of this church is full of important restorations: Pope Clement XI decided, in fact, at the beginning of the 18th Century, to renovate it further, and commissioned the work to Carlo Fontana, who rebuilt practically the entire interior. However, the vicissitudes of the Holy Apostles did not end here, and they resumed in the 19th Century, when Giuseppe Valadier was commissioned to design the neoclassical façade, completed in 1827 without respecting the original project to the letter. It is occupied by a large rectangular central window with two composite pilasters at the sides, which support the entablature with a long inscription.

THE INTERIOR OF THE BASILICA

The interior houses various artistic treasures, starting with the valuable relief placed on the right side of the portico, which depicts an imperial eagle framed by a crown of oak leaves, datable to the 2nd Century AD. Immediately below is a very worn marble lion, signed by a member of the famous Roman marble family, the Vassalletto.

Beyond the portico, you enter the three large naves, on which three chapels open on each side. The grandiose and aerial vault is entirely frescoed by Baciccio in 1707, and depicts “The Triumph of the Order of St. Francis“, while one of his pupils, Giovanni Odazzi, painted the fresco that adorns the vault of the presbytery, with a “Expulsion of the Rebel Angels“, conceived in full 18th Century spirit and executed two years later.

In the side chapels, other masterpieces of every era:

– the 15th Century tombs by the sculptor Andrea Bregno, among which stand out that of Pietro Riario (on the left side of the apse) and Raffaele della Rovere (in the crypt);

– the largest existing altarpiece in a Roman church, depicting the “Martyrdom of Saints Philip and James”, painted by Domenico Muratori in 1704;

– the first Roman work by Antonio Canova, the monument to Pope Clement XIV from 1789, with the Pope depicted in a solemn and authoritarian attitude, with his arm raised not to bless but to subdue, in order to highlight his great political attitude and strong-willed temperament.

The apse of the church was painted, by order of Pope Sixtus IV, by the artist Melozzo da Forlì, who depicted a shining “Christ in glory among angels“. Unfortunately, however, the work was dismembered in the eighteenth century, and is now split between the Quirinal (the figure of Christ) and the Vatican Art Gallery (the Musician Angels). If you want to see these last ones, please book the Vatican Museums Extended Tour, including the Painting Gallery.

THE VALENTINI PALACE

Opposite the short side of the square, once you have crossed the last stretch of Via IV Novembre, you will find yourself in front of an impressive building, which today houses the headquarters of the Prefecture and the Metropolitan City of Rome: the 16th Century Valentini Palace, built by Cardinal Michele Bonelli, nephew of Pope Pius V, nicknamed “Alessandrino” because he was originally from Alessandria.

The cardinal had carried out a great work of reclamation in that area, called by the people “the Pantano” because it was marshy, stretched between the Forum of Trajan and the Forum of Augustus, and during the works he had bought a house owned by the Boncompagni family. After demolishing it, he had a new building built on the same site for himself, and commissioned the project to the architect friar Domenico Paganelli.

Thanks to the large sums of money allocated by the rich cardinal, combined with the skill and talent of the architect, the building was completed in 1585 and three years later it was already inhabited by Bonelli.

In 1598 Cardinal Bonelli died, and the objects belonging to his rich art collections were inventoried by three famous artists: the Pomarancio, the Flemish Vincenzo Cobergher and his compatriot Paul Brill, who specialized in landscape painting. Among the assets accumulated by the cardinal were authentic masterpieces: paintings by Titian, Lorenzo Lotto, Bassano, Palma il Vecchio and many other great artists. His heirs, however, did not go to live in the sumptuous residence, which was therefore rented out, since at the beginning of the 17th Century the family’s economic conditions were not particularly prosperous.

Around the middle of the 17th Century another cardinal, Carlo, brought the house back to its former glory, and, based on the good habits of the Roman aristocratic families, he immediately thought of enlarging the palace, entrusting the work to the architect Francesco Peparelli and then, on his death (1676), to Michele Ferdinando Bonelli, who died tragically thirteen years later, falling from a window of the building. The palace was first sold to the Imperiali, who set up the important family library (24,000 volumes), and then, at the end of the 18th Century, to a wealthy banker, Vincenzo Valentini. He spent a fortune to enlarge it, and arranged his important collection of archaeological finds there: some statues of the collection can still be seen today in the beautiful porticoed courtyard, with 5 arches on the short sides and 9 on the long ones.

THE ROMAN DOMUS OF THE VALENTINI PALACE

During some excavation aworks in 2005, six meters below Valentini Palace’s floor, two noble residences dating back to the 4th century AD came to light: they were equipped with a private spa area, belonging to influential families of the time.

You can visit them booking your turn on the Official Website, enjoying so an incredible virtual reconstruction of the two houses, walking on a transparent flooring that will allow you to walk as if suspended on this extraordinary site.

Your itinerary now continues along the narrow Via dei Fornari, named after the University of Fornari (Bakers), which in 1507 had the Church of St. Mary of Loreto built at its own expense, with a small hospital attached.

This street today lies between the 16th Century Valentini Palace and the much more modern Palace of General Insurance, built in 1911, taking the Renaissance proportions of Venice Palace as a model. In Via dei Fornari lived the great Renaissance genius Michelangelo Buonarroti, whose house (which probably also served as a study for his pupil Daniele Da Volterra) was demolished to make way for the Palace, as remembered by a plaque on the wall.

At the end of the narrow street there is a unique view of the Forum of Trajan, dominated by the splendid column erected in 113 A.D. following the orders of the Emperor himself, who had the most salient episodes of the expeditions he had led against the Dacians celebrated there, eternally in marble.

THE CHURCH OF ST. MARY OF LORETO

Right in front of the column is the Church of St. Mary of Loreto, much criticized at the time of its construction. The church, in reality, is a small masterpiece by the Tuscan architect Antonio da Sangallo the Younger: on a massive square brick base, a high octagonal drum (also in brick) with elegant windows, which supports the dome, divided into eight segments. The building is located in the same place where there was another church, donated by Pope Alexander VI to the confraternity of bakers in 1500: only a valuable panel painted by an artist of the school of Antoniazzo Romano, depicting the “Madonna between Saints Sebastian and Rocco” and placed on the high altar, was saved from demolition.

Enter the church through a high portal surmounted by a triangular tympanum, which contains a valuable bas-relief with the “Madonna with Child and the Holy House“, attributed to Andrea Sansovino (1580).

The interior is octagonal feathered, with chapels and deep presbytery, with the vault decorated with golden stuccoes: on the walls, marble statues, including Duquesnoy‘s St. Susanna, considered his masterpiece (1630). Also noteworthy are the large canvases, by Cavalier d’Arpino, and the two boxes with organ from the 16th Century.

THE CHURCH OF THE HOLY NAME OF MARY

Almost attached to St. Mary of Loreto there is another church with a similar structure (for this reason they are called “the twin churches”). This is the Church of the Holy Name of Mary, built between 1736 and 1738 to replace an old small 15th Century church dedicated to St. Bernard. The company of the Holy Name of Mary, which had been formed in 1683 following the victory of the Christian army against the Turkish, needed a larger church, and entrusted the work to the French architect Antoine Derizet, who was inspired by the adjacent church.

The structure of the Name of Mary is indeed reminiscent of that of St. Mary of Loreto: here too you see a square base with rounded corners, divided by columns and ending in a high marble balustrade, decorated with statues. The interior, with a rather simple appearance, has an elliptical plan with seven chapels covered in polychrome marble: on the high altar, by Mauro Fontana, there is an ancient sacred image of the Virgin Mary, which comes from the oratory of St. Lawrence in Lateran.

Leave the “Twin Churches” and the splendor of the Forum of Trajan to walk again in the direction of the Trevi Fountain, taking Via di Sant’Eufemia and then the steep Via della Cordonata, which was one of the ancient routes that connected the top of the Quirinale with the plain of the Forums below. The “cordonates” were the routes with a paved bottom alternating with stone blocks, a procedure used to make the bottom less slippery and, consequently, easier to climb.

Once at the top of the “cordonata”, turn right towards Largo Magnanapoli, already examined in the previous itineraries. The large building at the corner of Via XXIV Maggio and Largo Magnanapoli itself is the Antonelli Palace, which now houses some offices of the Bank of Italy, and inside which you can see, with permission, a large arch made of tufa ashlars belonging to the Servian Walls, the oldest in Rome.

CHURCH OF ST. MARY OF CARMINE

Now take the narrow Via del Carmine, which leads into a small widening dominated by the façade of the small and little known Church of St. Mary of Carmine, suffocated by traffic and chaos in the centre of Rome.

Its construction was begun in 1605 by the confraternity of the Carmine, buying some barns owned by the Abbey of Grottaferrata. The works, sponsored by the munificent Cardinal Odoardo Farnese, were endless, and finished only in 1750. Unfortunately, in 1772, a terrible fire completely destroyed the church, which had to be rebuilt at the will of Pope Clement XIV, based on a project by the architect Alessandro Specchi.

The interior, with a single nave with barrel vault, has three altars and is decorated with fake stucco. On the high altar, at the centre of a ciborium composed of a tympanum supported by two columns, there is an 18th century statue of the “Madonna of the Carmelo“, in papier-mâché.

THE INAIL PALACE

Return now to Via IV Novembre, to observe the last stretch of the street, dominated by the imposing bulk of the INAIL Palace, built in 1936 by Armando Brasini on the site of the National Dramatic Theatre, demolished five years earlier.

The Theatre was built in 1888 by Francesco Azzurri, and its facade was reminiscent of the Paris Opera: during the construction work the workers found two splendid bronze statues, depicting a Boxer at Rest and a Hellenistic Prince, now exhibited in the National Roman Museum of Palazzo Massimo as two absolute masterpieces (visit it booking the Museums and Galleries Tour)

Unfortunately, the competition from the Quirino and Valle theatres, which enjoyed greater favour with the Roman public, together with the death of Eugenio Tibaldi, founder of the Society of the National Dramatic Theatre, resulted in the end of the Theatre.

VIA DELLA PILOTTA

Opposite the Waldensian Evangelical Church, built in 1883 to a design by Pandolfi, there is the picturesque Via della Pilotta, which creeps into the space between the Colonna Palace and the villa of the same name, climbing the slopes of the Quirinale and connected to the residence by four large arches built during the 18th Century.

On the left, at number 17, there is the entrance to the Colonna Gallery, of which we have spoken in the previous pages, followed by a Marian shrine of the 19th Century.

The street leads to the square of the same name, whose name, attested already at the beginning of the 16th Century, derives from the fact that the square was used for the game of the ball (the term “pilotta” is a deformation of the Spanish “pelota” which means “ball“).

The square, one of the most peaceful in the city, is dominated by the façade of the Palace of the Pontifical Gregorian University, built in 1927 by Giulio Barluzzi at the behest of Pope Pius XI, to permanently house (after various transfers, from the slopes of the Capitol to the Roman College) the ecclesiastical institution, founded in 1551 by St. Ignatius of Loyola with the precise aim of providing the clergy with adequate courses in theology and other humanistic disciplines.